In 1999 Ronald Searle was judged, by his fellow cartoonists, to be the greatest cartoonist of the 20th Century. It’s a judgement I thoroughly endorse, though as someone who was brought up on Searle, like most people of my generation born in the late 50s and early 60s, I thought distant worship would be as close as I ever got to him. After all, Searle famously scarpered when I was about one, so I, along with other British cartoonists, could only ever venerate him as the King Across the Water.

Still, when I was approached in 2005 to front a BBC4 documentary about Searle, I jumped at the chance, even though he made clear very early on he wanted nothing whatsoever to do the making of the film or anyone involved with it. That’s his prerogative, and my reverence for him includes a deep respect for his desire for a bit of peace and quiet. Nonetheless, the programme went ahead without him, and I enjoyed it for the most part (although, as I’d decided to speak to camera unscripted, to capture a greater sense of immediacy, there were occasions when the demands of the producer that I repeat a line 20 times meant that by the end I kept forgetting it, as well as forgetting what it could possibly mean.)

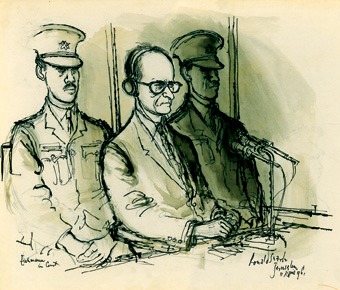

Part of the gig – part of the reason they’d got me to do it in the first place – was that, when pressed, I can draw a little bit like the master, and I did several pieces to camera sitting at a drawing board and replicating his style. One riff I went off on was the idea that Searle had invented his version of Hogarth’s famous “Line of Beauty”, which in his case was the “Angle of Beauty”, which I claimed was an acute angle of 37 degrees (I made that bit up, but you get the point) which can be seen repeated again and again in his depiction of feet and noses. I argued further that feet and legs – be they spindly, black-stockinged St Trinian’s legs, or the tree-trunk legs of the Masters at St Custard’s – were, for Searle, the windows to the soul.

All that may or may not be true, but I discovered a deeper truth when I was reproducing the standard Searle script for the “Entr’-Act” cards for the programme. Apart from the fact that each letter tended to twist my nibs into unusability, I soon realised something about that gnarled, nobbly lettering: that without the way Searle drew and wrote, most of the best British post-war cartooning would be unimaginable. Every line of Steadman’s or Scarfe’s had its origins in Searle’s blots. Those blots had shown us all the true path.

Anyway, we finished the film and it was duly broadcast – though in post-production I felt they added too many interviews about his life, and didn’t concentrate enough on his drawing, but what do I know? The production company sent him the film, and were greeted with silence. But unreciprocity from your gods is what you should expect, so I didn’t mind that much.

But then, a few weeks after the programme’s first transmission, I got a letter, sent to my home, addressed in a strangely familiar handwriting. It was a personal letter from Searle, thanking me for placing the garlands on his brow and apologising for the fact that he’s be dead by the time it was my turn. The letter is now framed and hangs in its place of honour next to the only Searle original my wife could afford to buy me. Better yet, in the few interviews he’s given since, he’s been kind and generous enough to say he likes my work. So happy 90th birthday, Mr Searle, from a very humble and grateful admirer…

Ronald Searle shows open in London

In the spirit of our recent coverage of the Ronald Searle exhibitions, we are pleased to publish Martin Rowson‘s article from the exhibition catalogue produced by the Cartoon Museum.

Bloghorn thanks The Cartoon Museum and Martin for permission to publish here in advance of tonight’s opening.

Tags

Latest Posts

Categories

Archives