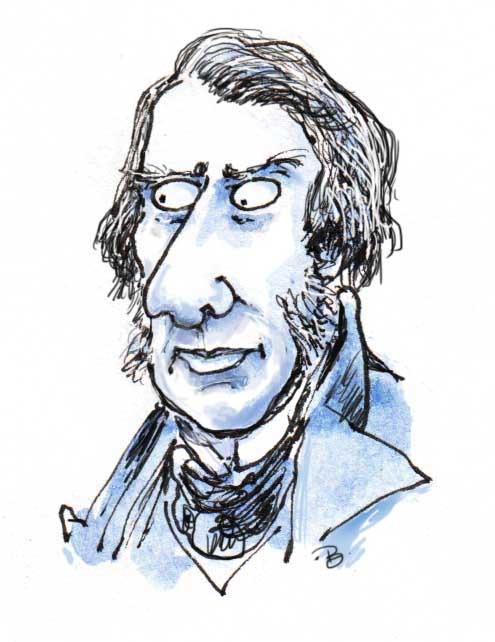

Caricature by © Rupert Besley

Rupert Besley writes:

…John Ruskin, that is. It’s his 200th birthday in February and there are events lined up to mark the occasion. One such is Chris Beetles’ forthcoming exhibition ‘Ruskin’s Artists’ (13 Feb-2 Mar), celebrating the work of those he cherished.

Helen Allingham ‘A Devonshire Cottage’ (from © Chris Beetles Gallery catalogue)

A shame for me I don’t have a spare £6.5k kicking around (so far, searches of jacket linings and sofa backs have brought in only one parking ticket and two licorice imps). With that kind of money, I’d be straight on to Beetles to buy up one of those Helen Allingham watercolours.

Ruskin was a polymath of the first order. It would take more than a page to do justice to the full range of his accomplishments. No mean artist himself, he achieved a great deal more as art critic than any since. He was hugely important in championing the genius of Turner and he played a big part in the 20,000 artworks of the Turner Bequest being saved for the nation. He greatly influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and was the inspiration behind the Arts & Crafts Movement that followed on (Wm Morris, CR Ashbee, Walter Crane etc, whose fine creations currently star in the BBC series on Fri nights).

Wasn’t it Brian Sewell who was given to making disparaging remarks about ‘mere cartoons’? This, certainly, is a BS quote: ‘there has never been a first-rank woman artist. Only men are capable of aesthetic greatness.’Refreshing, then, to see (as the Beetles Gallery blurb points out) that, well over a century back, Ruskin was equally supportive of female and male contemporary artists and that he considered Tenniel cartoons to contain ‘as high qualities as it is possible to find in modern art.’

Ruskin was much mocked in his time and repeatedly since. Leaving aside as less important his poor form in the marital bed, Ruskin the thinker and writer was way ahead of his time. Gandhi claimed Ruskin as a major influence, as had Tolstoy and the founders of the Labour Party. Outraged by the downsides of industrialisation, capitalism and urbanisation in full swing around him (ugliness, pollution, disconnect from nature and, above all, exploitation of and deterioration in quality of life for the working classes), Ruskin positively exploded with solutions, all of them still attractive today. Much of what he proposed had to await the arrival of the welfare state, but institutions that owed much to his thinking, such as the National Trust and the National Parks movement, came about in his lifetime or soon after. Other concepts that he worked on, like the greenhouse-effect and fractal geometry in nature, had to wait their time, some century and a half later.

Visionary, conservationist and social revolutionary, Ruskin put his ideas into practice where he could. Believing in the power of art and natural beauty to transform lives and restore human dignity, Ruskin taught a generation to see things differently. And he took on establishment snobberies that allowed intellectuals to look down on manual work. As Oxford’s first Professor of Fine Art, in 1874-5 he got undergraduates – including the young Oscar Wilde – to work on road-mending in N Oxford as a way to teach them the virtues of physical labour.

Ruskin’s high-minded aims in art rather outshine the me-me-me, self-publicising commercialism of so many artists fêted today. JR is one to remember, I reckon.

Hats off to JR

Caricature by © Rupert Besley

Rupert Besley writes:

…John Ruskin, that is. It’s his 200th birthday in February and there are events lined up to mark the occasion. One such is Chris Beetles’ forthcoming exhibition ‘Ruskin’s Artists’ (13 Feb-2 Mar), celebrating the work of those he cherished.

Helen Allingham ‘A Devonshire Cottage’ (from © Chris Beetles Gallery catalogue)

A shame for me I don’t have a spare £6.5k kicking around (so far, searches of jacket linings and sofa backs have brought in only one parking ticket and two licorice imps). With that kind of money, I’d be straight on to Beetles to buy up one of those Helen Allingham watercolours.

Ruskin was a polymath of the first order. It would take more than a page to do justice to the full range of his accomplishments. No mean artist himself, he achieved a great deal more as art critic than any since. He was hugely important in championing the genius of Turner and he played a big part in the 20,000 artworks of the Turner Bequest being saved for the nation. He greatly influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and was the inspiration behind the Arts & Crafts Movement that followed on (Wm Morris, CR Ashbee, Walter Crane etc, whose fine creations currently star in the BBC series on Fri nights).

Wasn’t it Brian Sewell who was given to making disparaging remarks about ‘mere cartoons’? This, certainly, is a BS quote: ‘there has never been a first-rank woman artist. Only men are capable of aesthetic greatness.’Refreshing, then, to see (as the Beetles Gallery blurb points out) that, well over a century back, Ruskin was equally supportive of female and male contemporary artists and that he considered Tenniel cartoons to contain ‘as high qualities as it is possible to find in modern art.’

Ruskin was much mocked in his time and repeatedly since. Leaving aside as less important his poor form in the marital bed, Ruskin the thinker and writer was way ahead of his time. Gandhi claimed Ruskin as a major influence, as had Tolstoy and the founders of the Labour Party. Outraged by the downsides of industrialisation, capitalism and urbanisation in full swing around him (ugliness, pollution, disconnect from nature and, above all, exploitation of and deterioration in quality of life for the working classes), Ruskin positively exploded with solutions, all of them still attractive today. Much of what he proposed had to await the arrival of the welfare state, but institutions that owed much to his thinking, such as the National Trust and the National Parks movement, came about in his lifetime or soon after. Other concepts that he worked on, like the greenhouse-effect and fractal geometry in nature, had to wait their time, some century and a half later.

Visionary, conservationist and social revolutionary, Ruskin put his ideas into practice where he could. Believing in the power of art and natural beauty to transform lives and restore human dignity, Ruskin taught a generation to see things differently. And he took on establishment snobberies that allowed intellectuals to look down on manual work. As Oxford’s first Professor of Fine Art, in 1874-5 he got undergraduates – including the young Oscar Wilde – to work on road-mending in N Oxford as a way to teach them the virtues of physical labour.

Ruskin’s high-minded aims in art rather outshine the me-me-me, self-publicising commercialism of so many artists fêted today. JR is one to remember, I reckon.

Tags

Latest Posts

Categories

Archives