Lilliput cover (Dec 1949) by Ronald Searle

Rupert Besley writes:

Some years back (50, to be precise) I spotted a small selection of Lilliput magazines from 1941-51 in a junkshop in Leeds. I bought all nine of them and have returned to them regularly since. This era was still the heyday of line illustration, which worked better than photographs on the cheap paper (all of it short in wartime) used by such publications. Radical and pioneering, Lilliput was as famous for its photographs, adventurous to the point of raunchy, as for its cartoons (it solved the problems of print quality by using different paper for text and photos).

In my few copies is to be found the work of many top cartoonists: Sprod, Starke, David Langdon, Brockbank, Anton, André François, ffolkes, Siggs, Osbert Lancaster, Hoffnung, Steinberg, Graham, Smythe, Scully, Acanthus, Emett… Later contributors included Thelwell and Heath. That’s quite some roll-call of talent. But it was the Searles that I bought my batch of magazines for. His work springs out from almost every copy I have, as it did for the artist himself in 1942. The story is well known, but bears repeating.

On leaving school at 15, Ronald Searle was already in 1935 getting a weekly cartoon into his local paper, the Cambridge Daily News. Four years on, having enlisted in the Territorial Army, Searle was doing camouflage work in Scotland (where he came across girls evacuated from St Trinnean’s School, Edinburgh) and firing off cartoons in different directions. One such (his first St Trinian’s cartoon) was taken for publication by Lilliput in Oct 1941, but Searle was not to know this – yet. His unit had already set sail for the Far East. In Feb 1942, under Japanese fire in Singapore, Searle chanced upon a discarded copy of Lilliput fluttering in the street. In it was his cartoon. There are barely words adequate to describe the extent of suffering then endured by Searle and his colleagues following capture and imprisonment or for the miracle of his survival.

Back in postwar UK, Searle found his work embraced with enthusiasm by Lilliput (and he married the editor). Lilliput is a treasure-trove of early Searles, but finding them is not always straightforward. For there was another artist, equally prolific, whose work could easily be mistaken for Searle’s at that time – so similar in fact that you need sometimes to check for signature. Searle was still at the start of his career, finding his own style, before going on to be arguably the greatest cartoon artist of the 20th century. No surprise that in his twenties Searle should have taken on some influence (distorted bodies, spindly limbs and telling eyes) from the work of James Fitton, well established on the magazine.

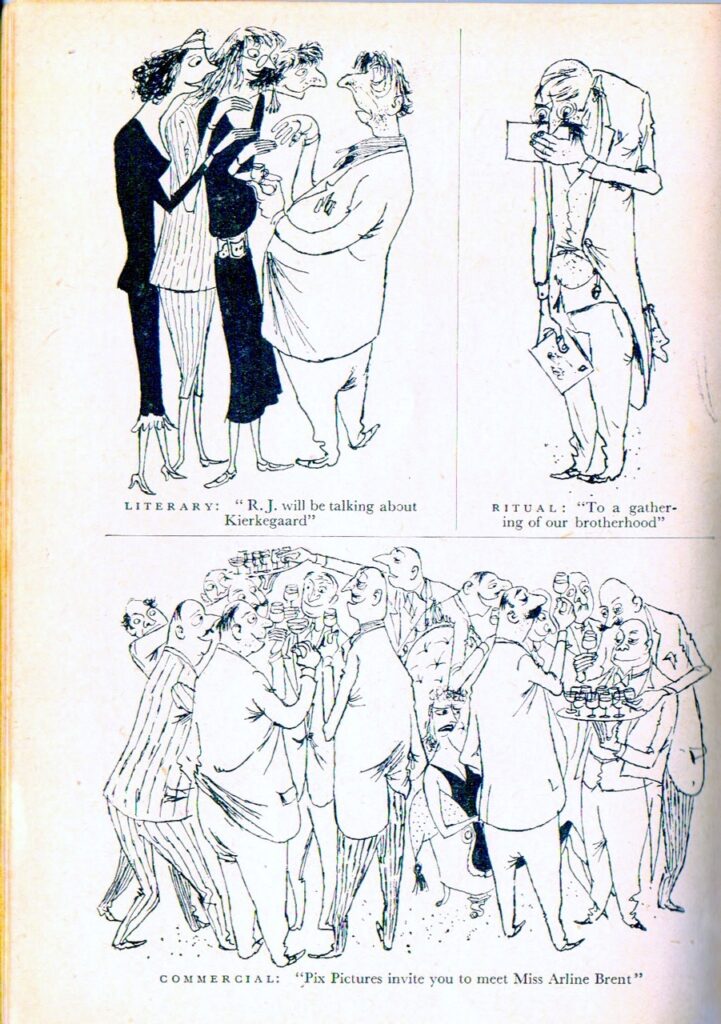

Lilliput (Dec 1949) Party Invitation cartoons by Fitton

James Fitton (1899-1982) had had a tough childhood in Oldham. His father, put to work at seven years old to clean around the workings of the cotton mill, had lost an ear when caught in the machinery. Determined to improve conditions, Fitton Snr became heavily involved in Trade Unionism and the Labour Movement, but got sacked in consequence. To support his family he had to work permanent night shifts incognito away from home. With a gift for drawing, the young James took evening art classes in Manchester alongside LS Lowry and the two stayed lifelong friends. Fitton moved south and his artistic career took off with illustrative work for London Transport, the Left Review and Lilliput. Later, he moved more into painting and other art-forms, ending as a Senior Member of the Royal Academy.

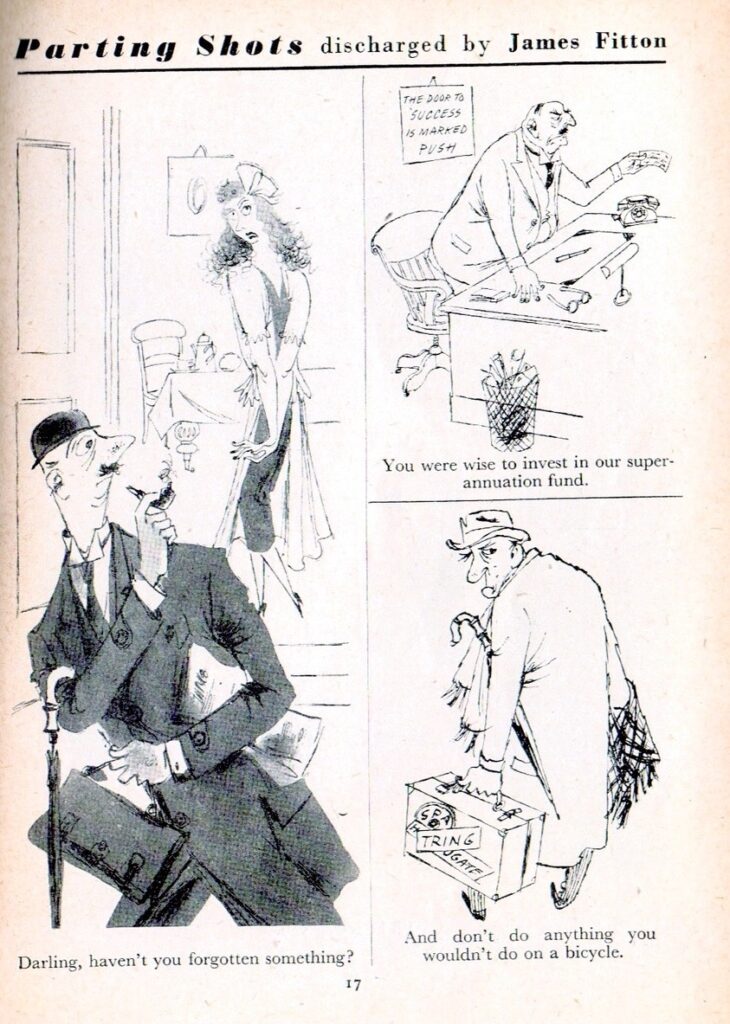

Lilliput (Aug 1950) Parting Shots cartoons by Fitton

That may be how James Fitton wished first to be remembered, but it seems a shame that in Artist Profiles online, as in Wikipedia, his cartoon legacy gets barely a mention. Could that be a case of old snobberies persisting that say Art matters, cartoons don’t? Ever the Cinderella, cartooning too often comes across as the art that dare not speak its name.

Giants from Lilliput

Rupert Besley writes:

Some years back (50, to be precise) I spotted a small selection of Lilliput magazines from 1941-51 in a junkshop in Leeds. I bought all nine of them and have returned to them regularly since. This era was still the heyday of line illustration, which worked better than photographs on the cheap paper (all of it short in wartime) used by such publications. Radical and pioneering, Lilliput was as famous for its photographs, adventurous to the point of raunchy, as for its cartoons (it solved the problems of print quality by using different paper for text and photos).

In my few copies is to be found the work of many top cartoonists: Sprod, Starke, David Langdon, Brockbank, Anton, André François, ffolkes, Siggs, Osbert Lancaster, Hoffnung, Steinberg, Graham, Smythe, Scully, Acanthus, Emett… Later contributors included Thelwell and Heath. That’s quite some roll-call of talent. But it was the Searles that I bought my batch of magazines for. His work springs out from almost every copy I have, as it did for the artist himself in 1942. The story is well known, but bears repeating.

Lilliput (Feb 1942) cartoon by Searle

On leaving school at 15, Ronald Searle was already in 1935 getting a weekly cartoon into his local paper, the Cambridge Daily News. Four years on, having enlisted in the Territorial Army, Searle was doing camouflage work in Scotland (where he came across girls evacuated from St Trinnean’s School, Edinburgh) and firing off cartoons in different directions. One such (his first St Trinian’s cartoon) was taken for publication by Lilliput in Oct 1941, but Searle was not to know this – yet. His unit had already set sail for the Far East. In Feb 1942, under Japanese fire in Singapore, Searle chanced upon a discarded copy of Lilliput fluttering in the street. In it was his cartoon. There are barely words adequate to describe the extent of suffering then endured by Searle and his colleagues following capture and imprisonment or for the miracle of his survival.

Lilliput (April 1952) cartoon by Searle

Back in postwar UK, Searle found his work embraced with enthusiasm by Lilliput (and he married the editor). Lilliput is a treasure-trove of early Searles, but finding them is not always straightforward. For there was another artist, equally prolific, whose work could easily be mistaken for Searle’s at that time – so similar in fact that you need sometimes to check for signature. Searle was still at the start of his career, finding his own style, before going on to be arguably the greatest cartoon artist of the 20th century. No surprise that in his twenties Searle should have taken on some influence (distorted bodies, spindly limbs and telling eyes) from the work of James Fitton, well established on the magazine.

Lilliput (Dec 1949) Party Invitation cartoons by Fitton

James Fitton (1899-1982) had had a tough childhood in Oldham. His father, put to work at seven years old to clean around the workings of the cotton mill, had lost an ear when caught in the machinery. Determined to improve conditions, Fitton Snr became heavily involved in Trade Unionism and the Labour Movement, but got sacked in consequence. To support his family he had to work permanent night shifts incognito away from home. With a gift for drawing, the young James took evening art classes in Manchester alongside LS Lowry and the two stayed lifelong friends. Fitton moved south and his artistic career took off with illustrative work for London Transport, the Left Review and Lilliput. Later, he moved more into painting and other art-forms, ending as a Senior Member of the Royal Academy.

Lilliput (Aug 1950) Parting Shots cartoons by Fitton

That may be how James Fitton wished first to be remembered, but it seems a shame that in Artist Profiles online, as in Wikipedia, his cartoon legacy gets barely a mention. Could that be a case of old snobberies persisting that say Art matters, cartoons don’t? Ever the Cinderella, cartooning too often comes across as the art that dare not speak its name.

Tags

Latest Posts

Categories

Archives