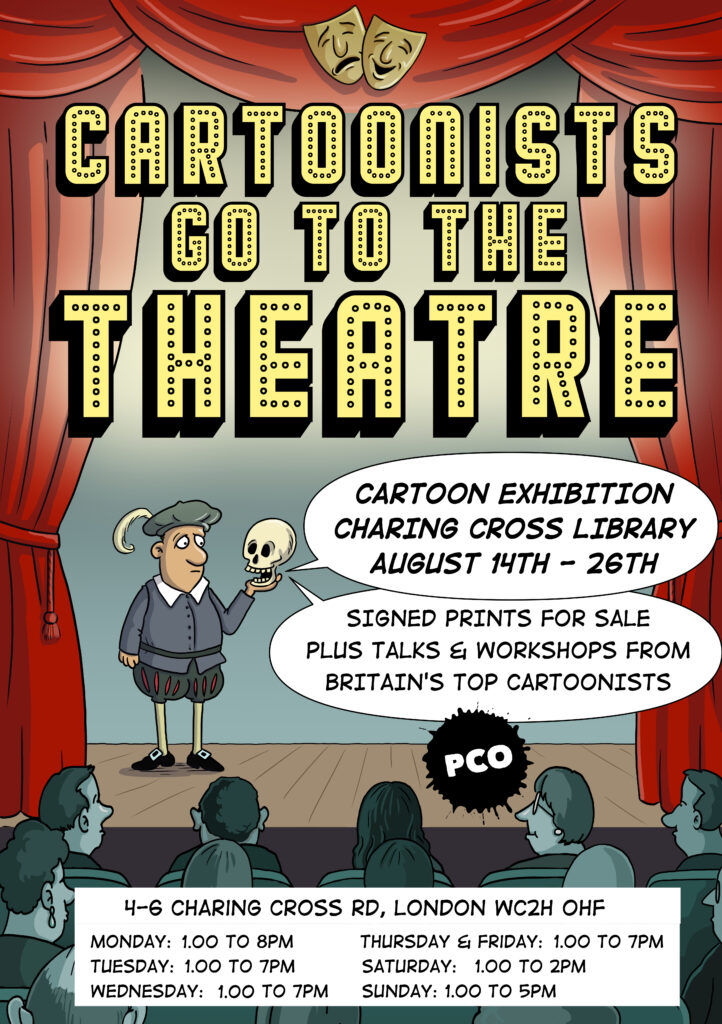

Cartoonists Go To The Theatre exhibition

Poster by © Clive Goddard The Surreal McCoy writes: Monday 14 August sees the opening of our CARTOONISTS GO TO THE THEATRE exhibition at Charing Cross Library, 4-6 Charing Cross road, London WC2H 0HF with the final curtain on Saturday 26th. Times below. Mon 14 1-4PM Tues 15 1-6PM Weds 16 12-2PM & 5-7PM Thurs […]

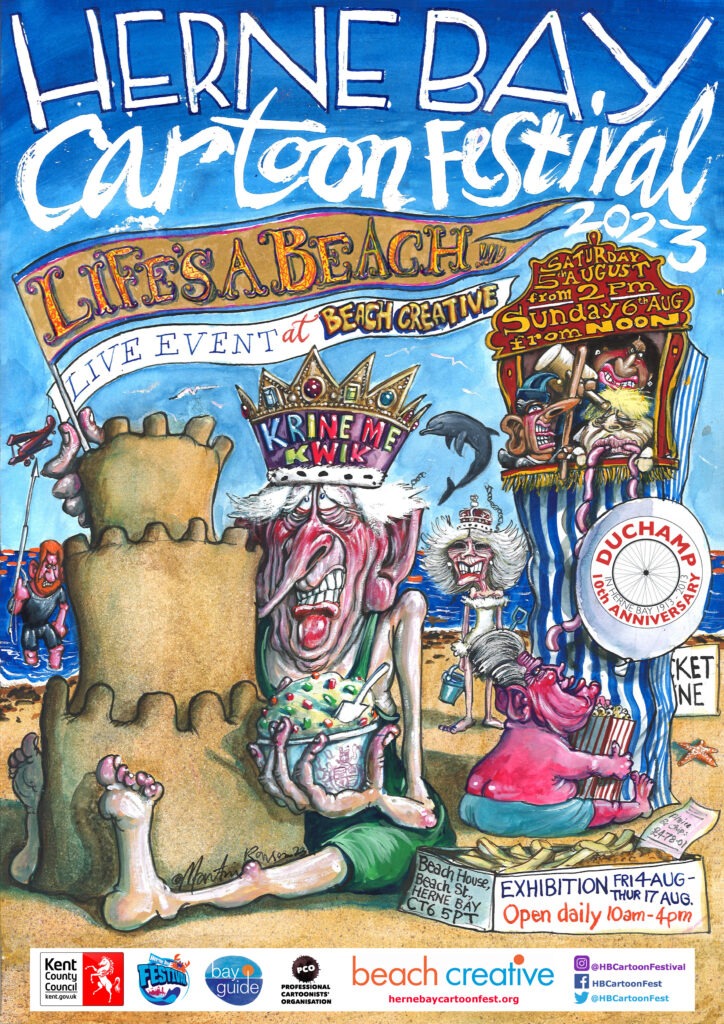

Herne Bay Cartoon Festival 2023 Preview

Poster cartoon © Martin Rowson Royston Robertson writes: Cartoonists will be heading to Kent next weekend for the annual Herne Bay Cartoon Festival, where they will be drawing live and raising a glass to ten years of the popular event. This year’s theme is “Life’s a Beach!”, a nod to the fact that the festival’s […]

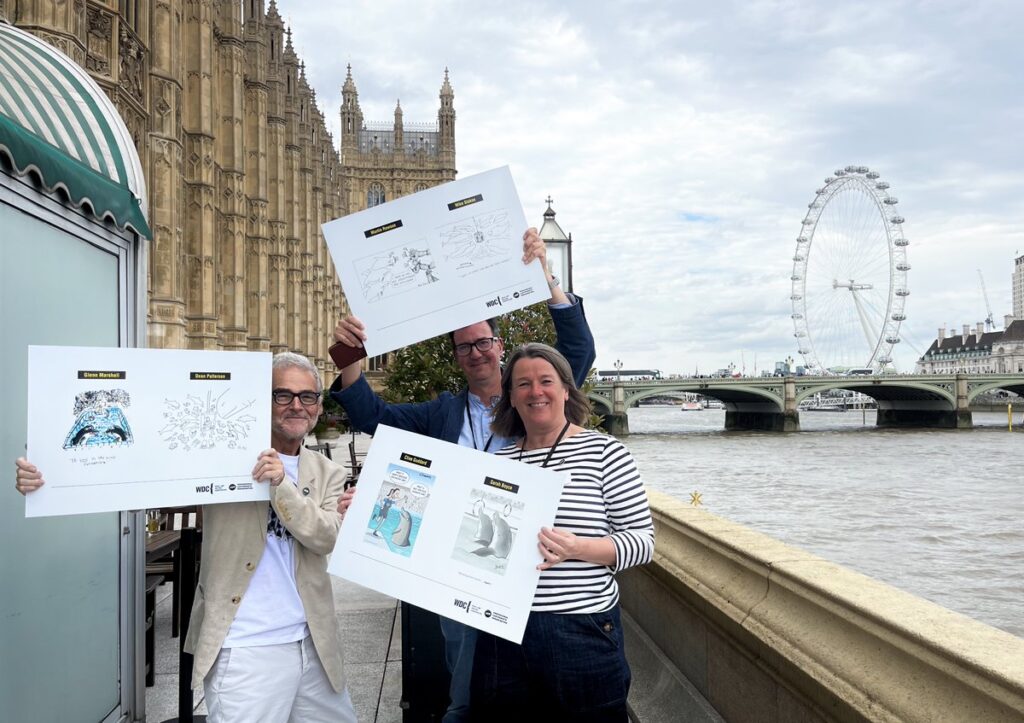

Cartoon Campaign Against Whale & Dolphin Cruelty

Mike Stokoe, Sarah Boyce and I weilding our cartoons outside the Commons with additional cartoons on the boards from Dean Patterson, Martin Rowson & Clive Goddard. Glenn Marshall writes: Procartoonists are pleased to be working in collaboration with Whale & Dolphin Conservation on a cartoon exhibition and campaign on the theme of captivity. We became involved […]

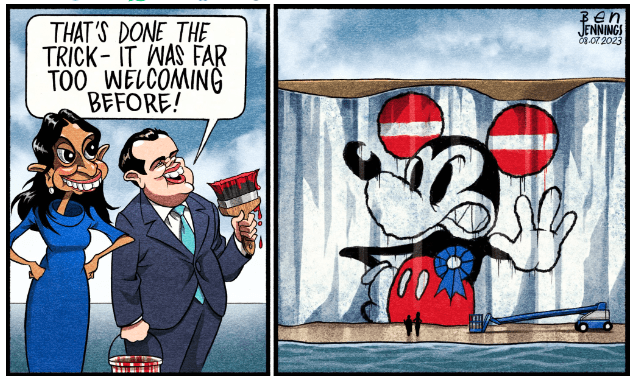

Government minister’s whitewash on childrens asylum centre.

Cartoon from The i by © Ben Jennings PCO Chair Clive Goddard writes: Earlier this month the Immigration minister Robert Jenrick ordered the overpainting of cartoon murals in two reception centres for the children of asylum seekers. This mean-spirited, pettiness rightly earned him a huge amount of public criticism from across the political spectrum. It […]

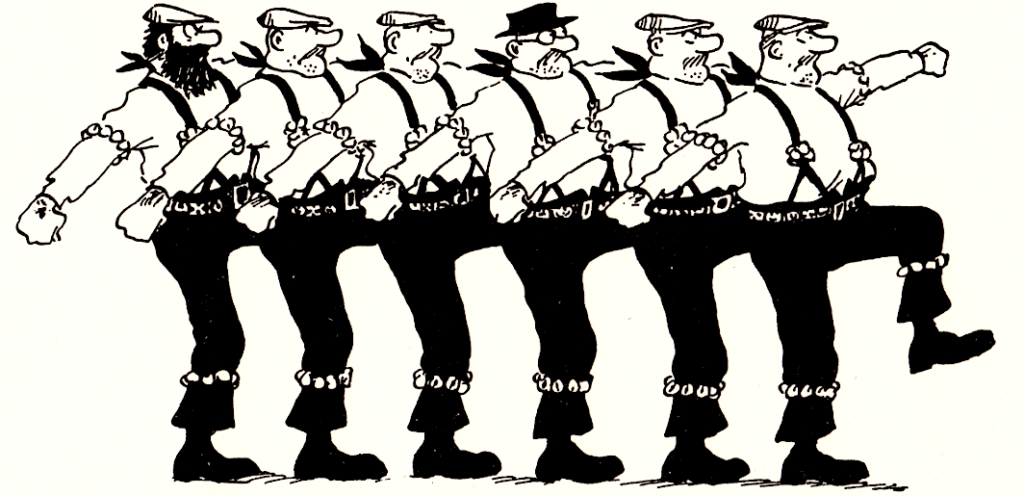

Bill Tidy (1933-2023) – A Tribute

Drawing of ‘The Cloggies’ from Bill’s long running Private Eye strip. Rupert Besley writes: It’s funny what sticks in the memory. First kiss, first day at new school, first pint, first dive into a pool… To which I’d add, first sight of a Bill Tidy cartoon. 1965. We’d just moved house and my brother came […]

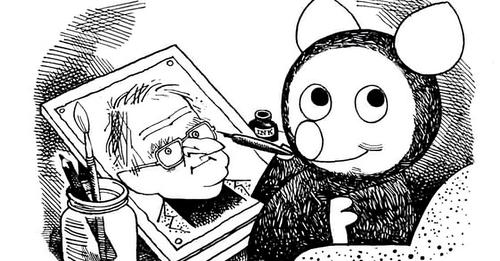

Wally Fawkes: an appreciation

Flook illustration Rupert Besley writes: Few people rise to the top of their profession. Very few are still in that position half a century on. And fewer still accomplish that in two careers at once. But this was the achievement of Wally Fawkes, loved and admired equally as jazz clarinettist and as the cartoonist […]

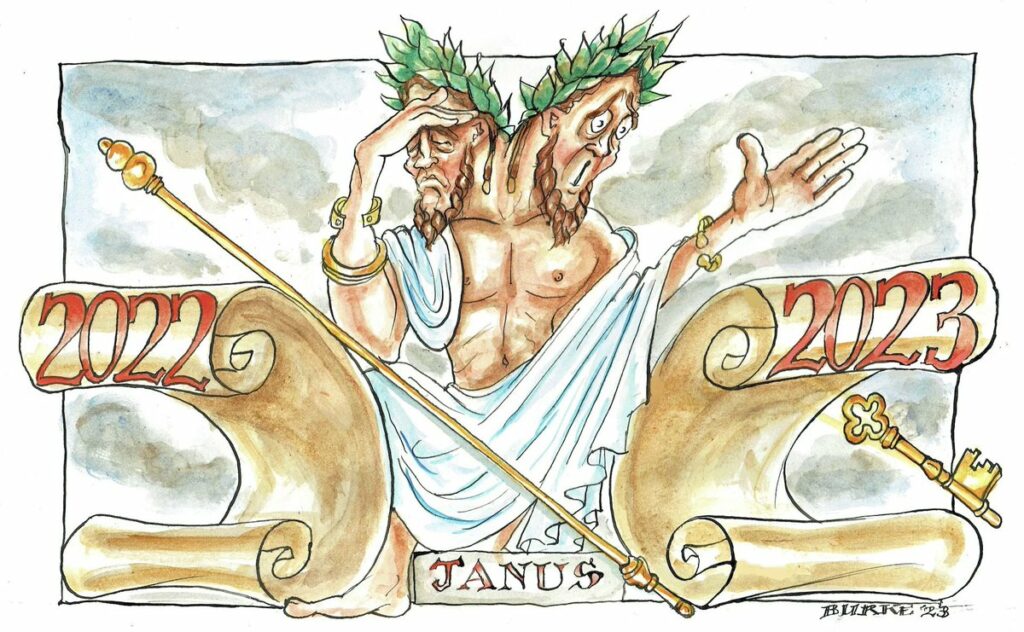

The PCO Cartoon Review of the Year 2022

Another year, another cartoon review featuring work from PCO members. As the world moves on from one disaster to another what more can you ask for than an emergency cartoon service attempting to defibrillate you at the start of the new year! Cartoon © Dean Patterson deAn set the tone for the year with this […]

The Shrewsbury International Cartoon Festival comes to an end

Big Boards in the town square 2006. Photo © Roger Penwill. Roger Penwill writes: The old maxim that all good things come to an end has become true for the Shrewsbury International Cartoon Festival. The sad and untimely loss of two key organisers just prior to the pandemic, Covid putting it’s oar in to disrupt planning […]

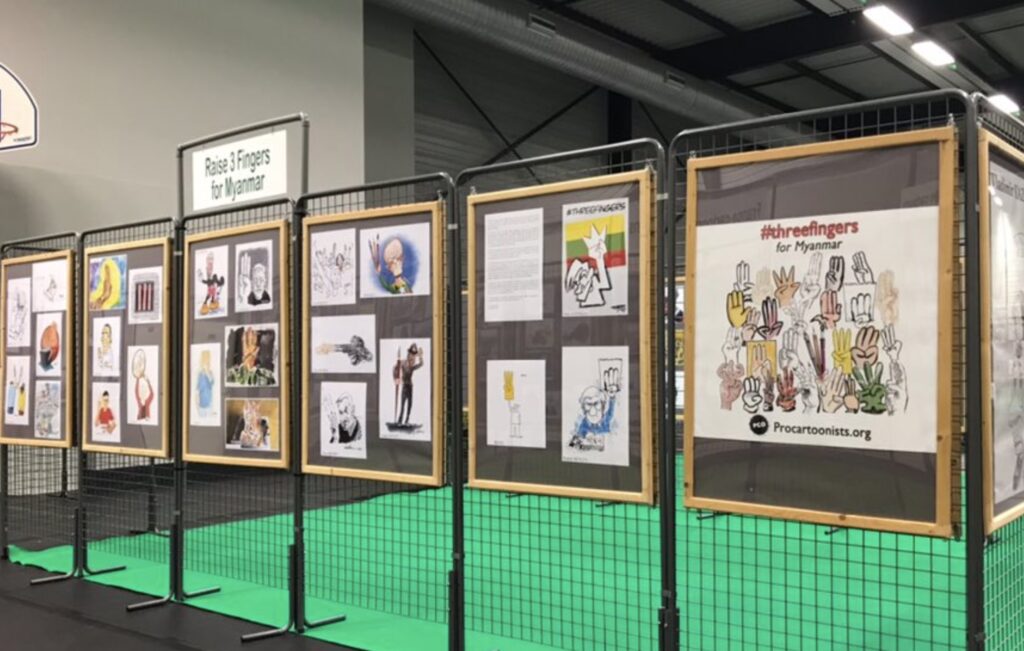

Raise Three Fingers for Myanmar at St Just Cartoon Festival

Our ‘Raise Fingers for Myanmar’ exhibition was recently shown at Saint-Just-le-Martel cartoon festival in France. This was coordinated by PCO Overseas committee member The Surreal McCoy. Cartoonist Rights Network International (CRNI) Executive Director and PCO Member Terry Anderson kindly sent photos of the displays. The exhibition poster Procartoonists Chairperson Clive Goddard wrote the following on the […]