Rupert Besley writes:

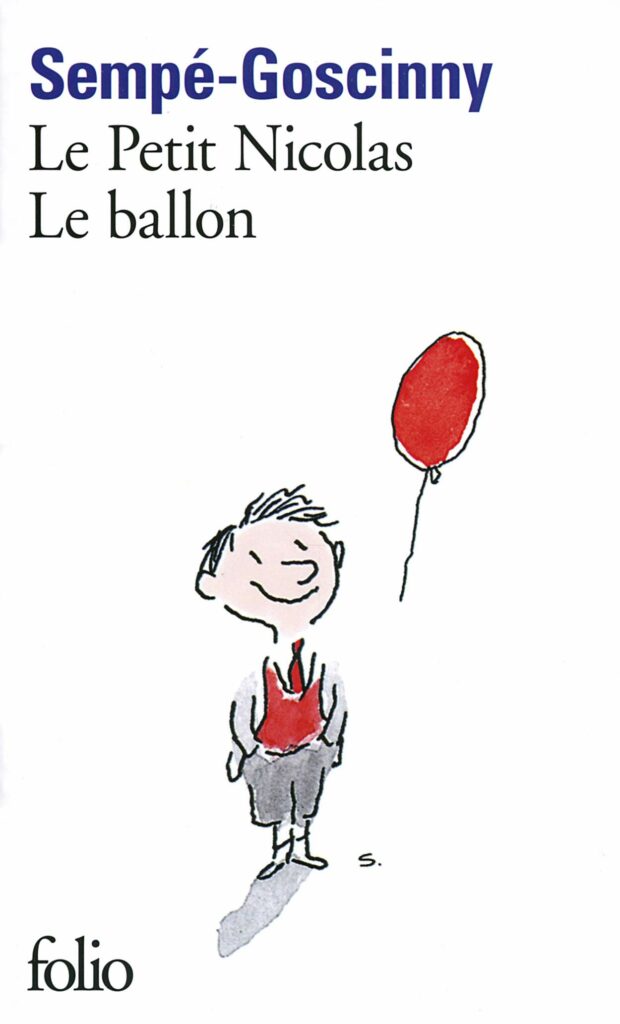

There’s a fine drawing on the cover of Le Petit Nicolas, Le Ballon which shows a small boy with an admiring smile watching as a slightly battered balloon goes off into the ether above. That’s a bit how the world is left feeling on hearing this week of the death at 89 of the great cartoonist (and illustrator of Nicolas) Jean-Jacques Sempé. Much sadness, of course, at the loss, but also a long and heartfelt smile, such was the warmth and wit, the charm and the joy that Sempé brought to all his work.

Little Nicolas was Sempé’s first big success, though it took time to build a following. Created in the 1950s in collaboration with Sempé’s good friend in Paris, René Goscinny (writer of Astérix and Lucky Luke), Nicolas went from comics to book form (13 books plus film, tv & video adaptations), translated into 30 languages and selling 15 million copies in 45 countries. The subversive schoolboy remains a national treasure in France, much loved for the mischief, mishaps and trouble he is forever into. It is a childhood idyll.

But Sempé’s childhood was far from idyllic. He’d had a rotten time. Born near Bordeaux, Jean-Jacques never knew his father, but was put instead into an abusive foster home. The violence continued when he was reclaimed 3 years later by his mother and an unhappy stepfather, whose days out selling anchovies and pickle from his bicycle mostly ended in alcohol and rows. ‘They were mad, poor things,’ said Sempé. The drawings came in place of what he had missed out on.

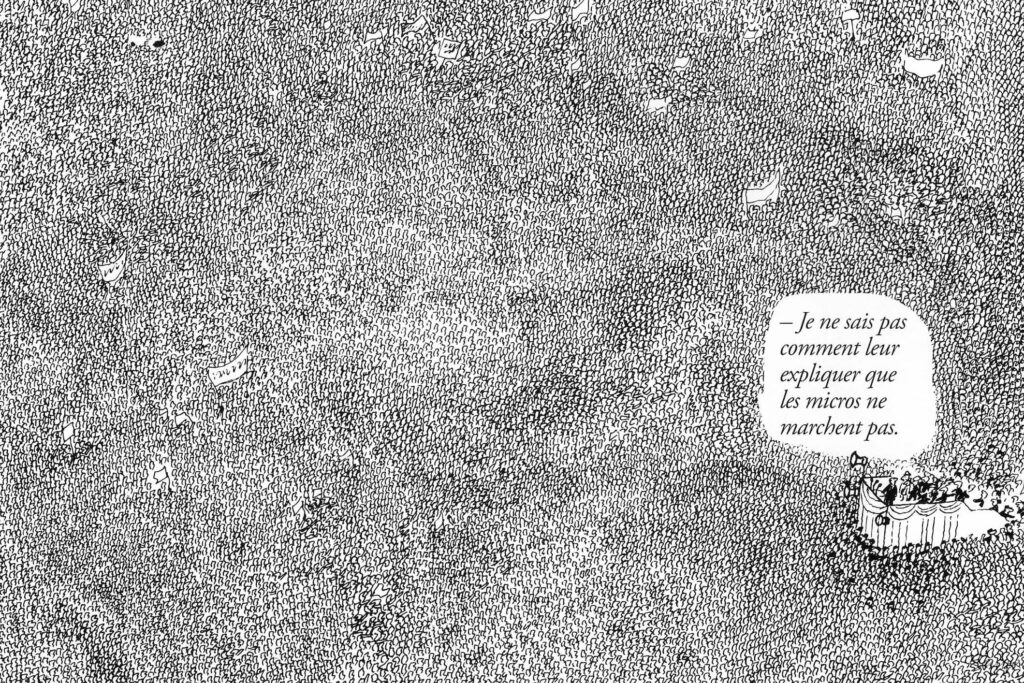

Caption reads: ‘I don’t know how to explain to them that the mikes aren’t working.’

Like so many cartoonists (there must be a link there), Sempé dreamed of becoming a jazz musician, another Duke Ellington. Instead he was out door-to-door selling toothpaste powder from his bicycle and later delivering wine. Having dropped out of school, he went on to be discharged from the army that he had joined under-age.

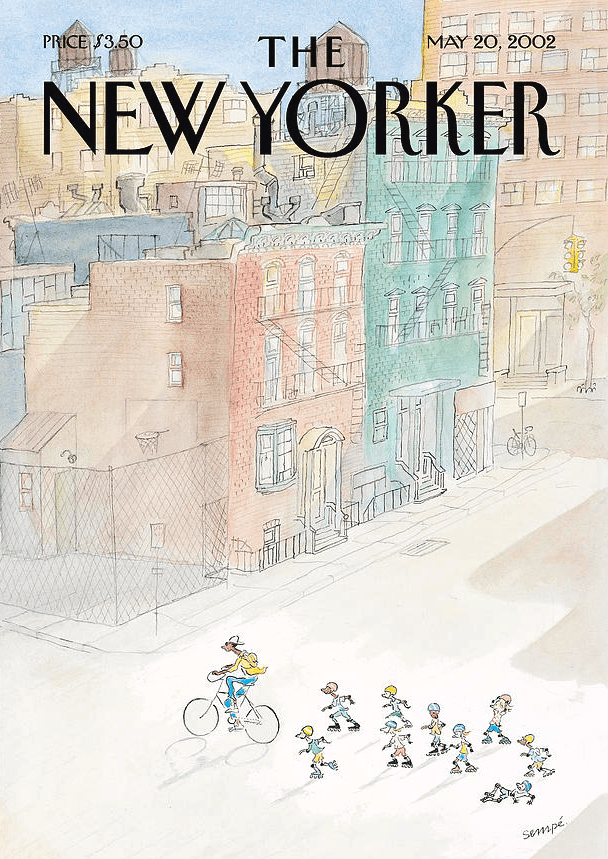

Self-taught as a cartoonist, Sempé never found drawing easy and often it eluded him. It was all hard graft, not talent, he reckoned, claiming he could spend 3 weeks on not getting a drawing right. But these always were right, just right. Neither laboured nor overworked, his drawings skip and dance off the page, with a lightness of touch and a joy in creation. Sempé completed well over 100 covers for The New Yorker, a record not yet matched by any other artist.

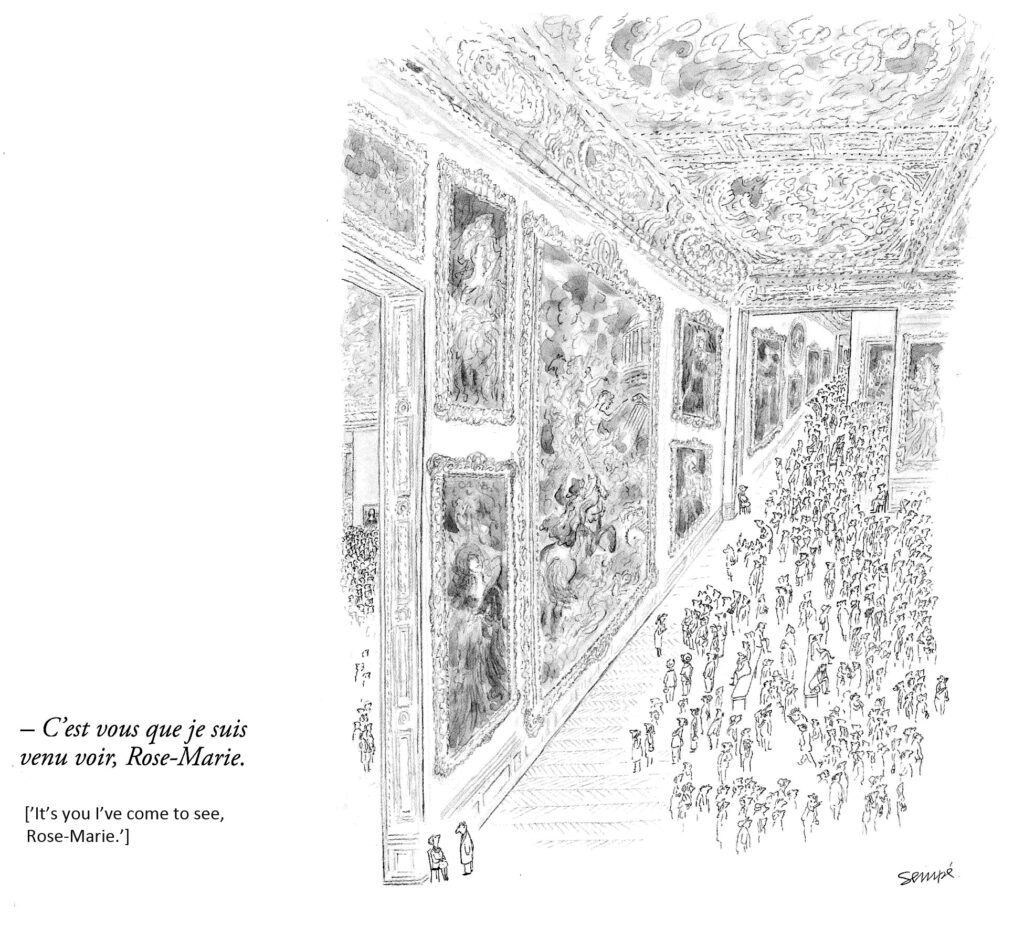

When he used colour, it was often to create a memorable setting (landscape, sea, cityscape, grand interior) that was itself a kind of character and participant in the action of the cartoon. Increasingly the figures he placed in such settings got smaller and smaller. But, Sempé insisted, ‘My people aren’t small, it’s the world that is big.’

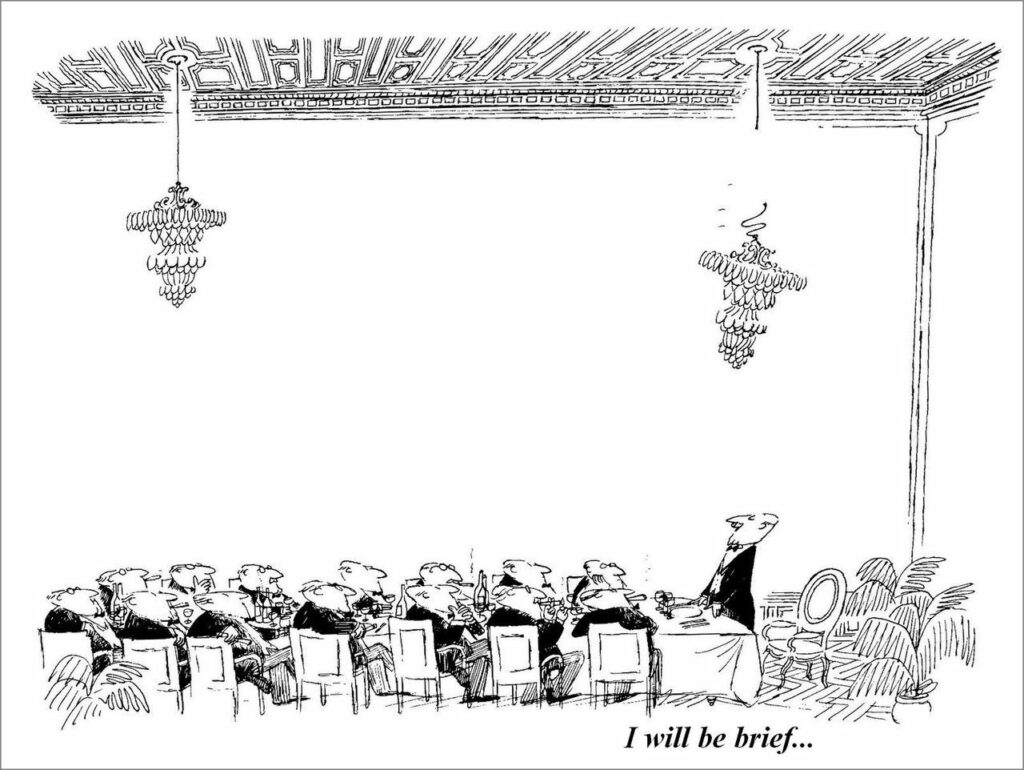

What grabbed Sempé was the little ironies of life and what makes people tick. In interview he said he was something of a dreamer, out to stir the imagination, to capture a mood and put on paper invisible feelings. But, above all, it was the mystery of people’s lives that fascinated him. In his work are whimsy, poetry, nostalgia and an undeniable Frenchness. And there are great gags too.

Bicycles feature much in his artwork, as do all kinds of performance (dancing classes, churches, music practice, art galleries, empty stages). Huge crowd scenes became something of a signature theme, along with neat juxtapositions, but just as often his cartoons (many of them captionless) made clever use of empty space. Much of Sempé’s humour has to do with subtleties and the small things in life – his first two cartoon collections were titled Nothing Is Simple and Everything Is Complicated.

Great artists (which does, of course, include cartoonists, writers, musicians and all the rest) create their own worlds, instantly recognisable and distinctive, embodying all that they see and feel. The world of Sempé is classic and timeless, one that will live on for generations to delight in and enjoy.

Sempé The Best

Rupert Besley writes:

There’s a fine drawing on the cover of Le Petit Nicolas, Le Ballon which shows a small boy with an admiring smile watching as a slightly battered balloon goes off into the ether above. That’s a bit how the world is left feeling on hearing this week of the death at 89 of the great cartoonist (and illustrator of Nicolas) Jean-Jacques Sempé. Much sadness, of course, at the loss, but also a long and heartfelt smile, such was the warmth and wit, the charm and the joy that Sempé brought to all his work.

Little Nicolas was Sempé’s first big success, though it took time to build a following. Created in the 1950s in collaboration with Sempé’s good friend in Paris, René Goscinny (writer of Astérix and Lucky Luke), Nicolas went from comics to book form (13 books plus film, tv & video adaptations), translated into 30 languages and selling 15 million copies in 45 countries. The subversive schoolboy remains a national treasure in France, much loved for the mischief, mishaps and trouble he is forever into. It is a childhood idyll.

But Sempé’s childhood was far from idyllic. He’d had a rotten time. Born near Bordeaux, Jean-Jacques never knew his father, but was put instead into an abusive foster home. The violence continued when he was reclaimed 3 years later by his mother and an unhappy stepfather, whose days out selling anchovies and pickle from his bicycle mostly ended in alcohol and rows. ‘They were mad, poor things,’ said Sempé. The drawings came in place of what he had missed out on.

Caption reads: ‘I don’t know how to explain to them that the mikes aren’t working.’

Like so many cartoonists (there must be a link there), Sempé dreamed of becoming a jazz musician, another Duke Ellington. Instead he was out door-to-door selling toothpaste powder from his bicycle and later delivering wine. Having dropped out of school, he went on to be discharged from the army that he had joined under-age.

Self-taught as a cartoonist, Sempé never found drawing easy and often it eluded him. It was all hard graft, not talent, he reckoned, claiming he could spend 3 weeks on not getting a drawing right. But these always were right, just right. Neither laboured nor overworked, his drawings skip and dance off the page, with a lightness of touch and a joy in creation. Sempé completed well over 100 covers for The New Yorker, a record not yet matched by any other artist.

When he used colour, it was often to create a memorable setting (landscape, sea, cityscape, grand interior) that was itself a kind of character and participant in the action of the cartoon. Increasingly the figures he placed in such settings got smaller and smaller. But, Sempé insisted, ‘My people aren’t small, it’s the world that is big.’

What grabbed Sempé was the little ironies of life and what makes people tick. In interview he said he was something of a dreamer, out to stir the imagination, to capture a mood and put on paper invisible feelings. But, above all, it was the mystery of people’s lives that fascinated him. In his work are whimsy, poetry, nostalgia and an undeniable Frenchness. And there are great gags too.

Bicycles feature much in his artwork, as do all kinds of performance (dancing classes, churches, music practice, art galleries, empty stages). Huge crowd scenes became something of a signature theme, along with neat juxtapositions, but just as often his cartoons (many of them captionless) made clever use of empty space. Much of Sempé’s humour has to do with subtleties and the small things in life – his first two cartoon collections were titled Nothing Is Simple and Everything Is Complicated.

Great artists (which does, of course, include cartoonists, writers, musicians and all the rest) create their own worlds, instantly recognisable and distinctive, embodying all that they see and feel. The world of Sempé is classic and timeless, one that will live on for generations to delight in and enjoy.

Tags

Latest Posts

Categories

Archives